We know that Republicans and Democrats talk differently, but what’s the best way to describe these differences? Commentators note the relative darkness of the Republican National Convention and the focus on optimism and higher production quality for the Democratic National Convention. Looking at the words speakers use helps–but you can’t just use simple frequency (for details, check out the methodology section at the bottom).

The major differences

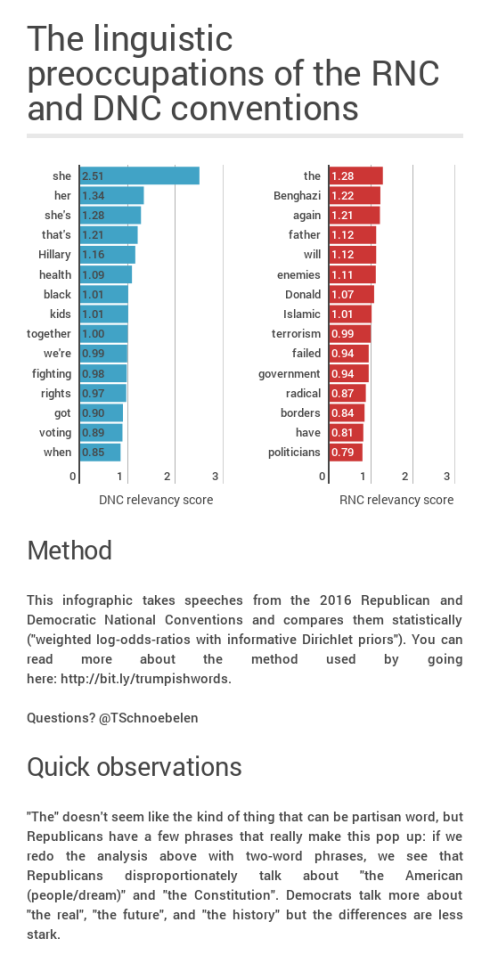

I’ve listed the top 15 words most characteristic of each convention, but I believe they boil down to the difference between “failed” and “fighting”. Consider some of the words that are firmly on the Republican side: government, failed, and politicians.

Failure is, of course, negative. You could consider government and politicians to just be neutral nouns, but that’s not how they are used by Republicans. And it seems that Democratic speakers are sensitive to this since they tend to avoid these words–there were 61 uses of government at the RNC but only 10 at the DNC. There were 19 occurrences of politicians at the RNC but only one at the DNC (that’s Obama and he’s using it negatively, too). But there are two ways of looking at this: the Republicans have seized them for negative purposes…and the Democrats have ceded them to anti-government/anti-politics forces on the right.

Meanwhile, fighting emerges as an important Democratic word. It’s not that the count is huge here–40 DNC uses versus the Republicans’ 6. But that it is indicative of a dominant framing. The past tense of this word is also characteristic of the DNC–Hillary Clinton and others are described by the battles they have fought (34 uses at the DNC, 5 at the RNC). This is a contrastive analysis, so it’s worth pointing out that Hillary Clinton has a longer career in politics than Donald Trump and his past work isn’t usually described in terms of battles, with perhaps one major exception.

For the Democrats, joint action also seems to be highly relevant–voting for instance or together, which is used regularly without being in the campaign motto, stronger together (stronger is also more of a DNC word than an RNC word–it scores 0.64 in Democratic relevance). Together was used 95 times at the DNC, only 27 times at the RNC. That said, the phrase stronger together only occurred 13 times at the DNC, once at the RNC. The great again part of Trump’s campaign motto occurred 24 times at the RNC, 6 times at the DNC.

Other differences include:

- Republicans often invoke Benghazi and terrorism (Benghazi, enemies, Islamic, terrorism, radical)

- Republicans frame immigration/terror in terms of borders

- Children of nominees don’t usually have as prominent a role as they did at the RNC: father occurs 56 times in 2016 RNC speeches. That said, it’s the Democrats who focus on kids (61 uses at the DNC, 14 at the RNC–child and children also skew strongly Democratic)

- Among the issues that Democrats focus on are health care/insurance, issues of social justice and gun control, which barely misses being in the infographic

- The Democrats tend to be more colloquial–the conventions are about equal in their use of we, but the Democrats are much more likely to use contractions we’ve and we’re as well as she’s and that’s. The Democrats also use got (usually got to) while the Republicans use have (though the strongest phrase for them is, have been).

- Ben Zimmer points out that researchers have found that the correlates with “high psychological distance”. It may also correlate with more older male speakers. Check out the Language Log for some other thoughts.

Going beyond words

I could also give you the two-word phrases that pop out, but let me just summarize those.

For the Republicans:

- Trump will

- my father

- our enemies

- Donald Trump

- he will

- American Dream

- no longer

- who will

- great again

For Democrats:

- she knows

- fighting for

- each other

- she was

- that’s why

- First Lady

- health care

- when she

- with her

Methodology and data

This post uses techniques described in Monroe et al (2008), a paper that pursued this as a question of methodology. In their paper, one of the prime examples was how Democrats and Republicans in Congress talk about issues like abortion.

The main point of Monroe et al is that you need to figure out some way to contrast two categories against each other and some background information–for example, Republican speeches on abortion versus Democratic speeches on abortion, with a background of everything else that Republicans and Democrats talk about. Technically speaking, I’m using weighted log-odds-ratios with informative Dirichlet priors. I call these “relevancy scores” in the infographic.

For the data, I took 50 speeches from this year’s RNC (50,191 words), 45 speeches from this year’s DNC (53,994 words), and 47 speeches from the past (180,719 words). DNC speakers use more words overall and their sentences are longer, too.

For the 2016 convention speeches, I used all of the speeches that the two parties made available via Medium, but for the prime-time speeches, I made an effort to get actual transcripts (removing annotations about applause, laughter and chants from the audience).

For setting “priors”, I used these word counts plus data from the recent and not-so-recent past. The past data is made up of: (a) all nominees’ speeches back to Carter and Reagan in 1980, (b) all the spouses’ convention speeches back to 2000–except for Tipper Gore’s, let me know if you can find a transcript for that, and (c) all the public speeches recorded for every Republican/Democratic presidential candidate between Jan 2016 and the conventions, as provided by The American Presidency Project.

“Donald” is not an important word in prior conventions, so it is characteristic of the current year and the RNC, in particular (218 uses of it in the RNC, 142 in the DNC speeches). The same goes for “Hillary” (300 times in the DNC speeches, 181 in the RNC). And that’s also one of the reasons that “she” appears as a major keyword for the DNC (419 occurrences in the DNC , 142 in the RNC). Clinton is the first nominee of a major party whose pronoun of choice is “she”. But there’s not much special about “he” (234 in DNC, 288 in the RNC). Yes, “he” often refers to Donald Trump in the conventions this year, but it could also refer to all the other nominees that both parties have fielded.

Leave a comment